Image credit: Unsplash

With its pristine beaches and luxury, the Hamptons has long shone as a coveted summer haven for New York’s elite. However, behind the opulent mansions and posh boutiques lies a starker reality, one not regularly splashed across magazines. With the pandemic pushing affluent New Yorkers to make the Hamptons their permanent residence, the demographic shift has intensified, spotlighting issues long-simmering beneath the surface.

According to US census data, the population of East Hampton alone saw a jump of over 30% between 2010 and 2021. This demographic shift brought new businesses, higher school enrollments, and more demands on public services. But how does this landscape shift affect locals, especially those not swimming in affluence?

Miles Maier’s experience sheds light on this often-overlooked segment of the Hamptons. Having lived almost his entire life in East Hampton, this 37-year-old public-sector employee encapsulates the challenges of residing in a place increasingly aligned with luxury. “Growing up, my parents were part of an affordable housing lottery. The Hamptons of the ’80s and ’90s felt different,” Maier shared with a FastCompany staff writer.

Post high school, without the lure of college or a clear career path, Maier found employment with the marine patrol department, maintaining equipment. Two decades on, he is still in the same job. Yet, the monetary compensation doesn’t match the spiraling living costs. “Rent for a basic place was around $800 when I graduated. Now, finding something under $2,500 is a challenge,” he points out.

The repercussions of this financial strain extend beyond just housing. As Maier explains, soaring prices alienated locals from even essential commodities. “It’s almost a joke among us now. If you see people walking down the street with shopping bags, you know it’s summertime because local people don’t buy things in the village,” Maier notes. It’s ironic, but while booming with business, the region seems increasingly inhospitable to its native residents.

“You depend on the workforce to keep the community alive and going,” Maier adds. “When you realize people can barely keep their head above water financially, it’s like a bad tradeoff. We’re here to ensure this town is here for everybody wanting to come out on vacation. Looking at compensation and cost of living, you go: Well, how is that even possible?”

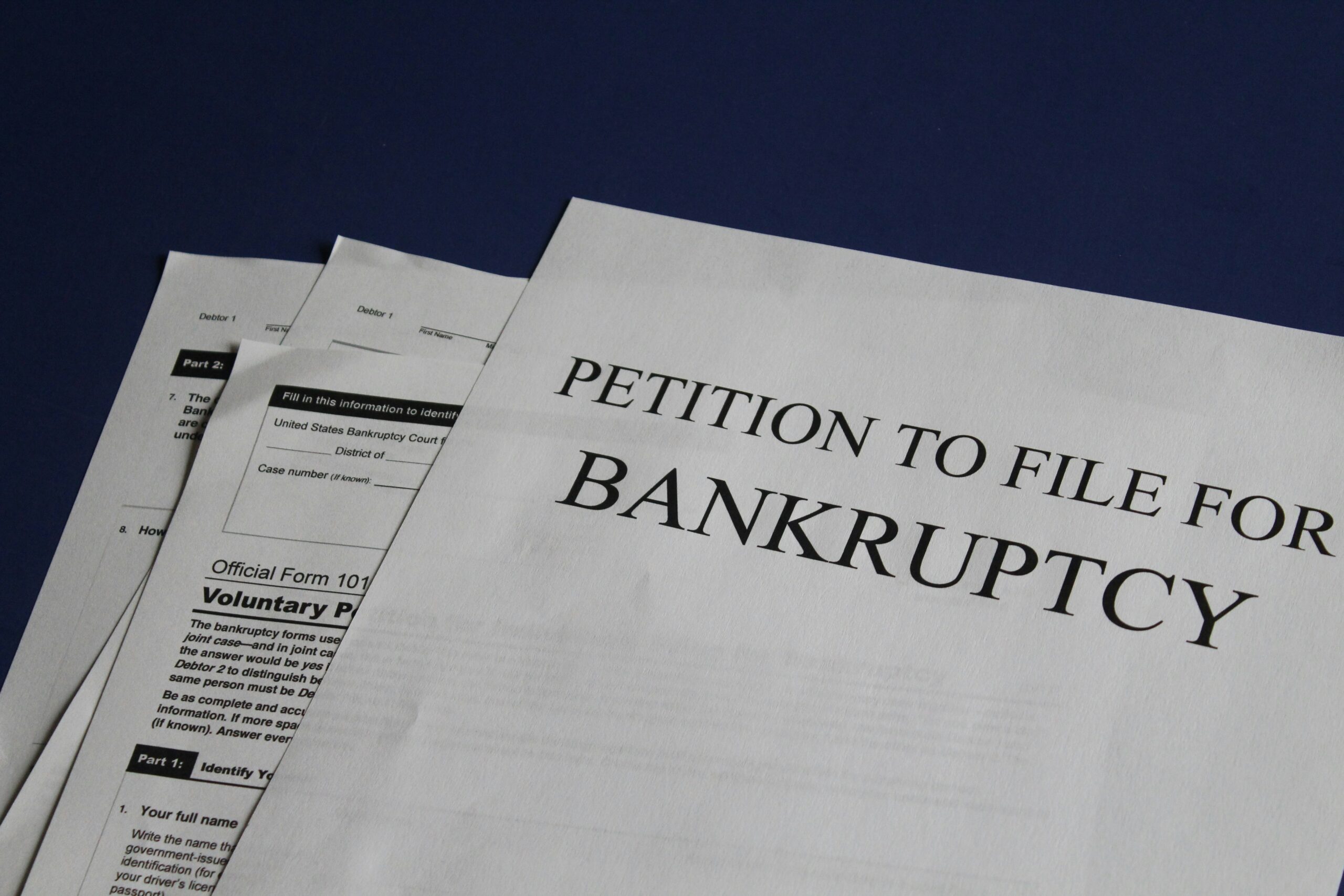

For Maier, achieving an annual salary of $60,000 took nearly two decades, a sum that seems paltry against the backdrop of the Hamptons’ exorbitant living standards. “I’m fortunate. I share a place with a friend; his mother is our landlord, so we have a perfect thing going,” he explains. “If I couldn’t live with a friend, I would have probably gone back to my parents’ house because I honestly couldn’t afford to rent a place anywhere else.”

But what of the future? With the dream of homeownership looking increasingly unattainable and the prospect of raising a family in such a situation bleak, many like Maier are at a crossroads. “The dream is not just about owning a home. It’s about building a life, a future. But sometimes, you wonder if it’s time for a change.” As the region evolves, the question remains: Will it make room for its heart, the local workforce, or will it be an unfortunate casualty of unchecked affluence?